Filtering by Tag: pediatric sports medicine

Pointing Out the Top 10 Pediatric Sports Musculoskeletal Injuries

The Top 10 Sports Musculoskeletal Sports Injury list is a ranking that I'm guessing most athletes don't want to make, and most parents don't want to miss.

How to best know if you belong on this list?

Trust your finger tips.

Speaking at the 2016 American Academy of Pediatrics National Convention and Exhibition, I was asked along with good friend and colleague Hank Chambers to share insight on identifying and managing the Top 10 Pediatric Sports Musculoskeletal Injuries with a Case-Based Review.

Our Top 10 aptly started at the top of the body (neck) and ran down to the bottom (foot/ankle) with several injuries in between.

We looked at:

- stingers

- shoulder pain

- elbow injuries

- wrist injuries

- low back pain

- hamstring avulsion injuries

- acute knee injuries

- shin pain

- ankle sprains

- heel pain in growing children.

Some were fairly serious and activity threatening, others were more of a nuisance.

A pretty diverse offering of injuries, so one would tend to think that there would be little that actually brings them together.

However, for those listening to the talk, they heard us mention a similar refrain over and over again.

The value of your finger tip.

In helping to determine a type of pain that merits medical attention in the first place, and helps sort out the particular diagnosis, the more localized the pain, the greater the potential concern.

For example,. if a child is reporting pain in the lower leg and uses a wave of the hand to indicate that the discomfort runs along the entire inner shin, then there is one level of concern.

However, if that same child takes the tip of their index finger and points directly and emphatically to a single spot on the inside of the shin bone, my concern is amped up several degrees.

While none of us have x-ray vision, that finding of finger-tip pain is a pretty good surrogate and does tend to correlate with a higher potential of a bone injury, be it a fracture, stress injury, or damage to a apophysis where a tendon attaches to a bone growth region.

So, no matter the body part, from elbow to wrist to foot or ankle, if any young athlete opts to use a finger tip to identify their pain, then use your finger tips to dial up your sports medicine specialist and seek out immediate and appropriate evaluation.

Back Pain with Volleyball Serving or Hitting? Look at Shoulder Function for Possible Cause

Whether you are a junior level or even an Olympic caliber volleyball player dealing with back pain during serving or hitting, chances are that shoulder mechanics are part of the problem.

Starting the serving or hitting motion requires both extension (leaning backward) and rotating or turning of the lower back in the direction of ball contact. For a right handed hitter or server, that would mean having the trunk and lower back rotate toward the right.

Dave Smith (#20) in early hitting phase shoulder position

Finishing a serve or hit requires rotation of the lower back away from the side of ball contact. Again, for that right handed hitter or server, that would mean having the trunk and lower back rotate towards the left after ball contact.

Kim Hill (#15) with late hitting phase shoulder position

This normal flow of movement puts localized stressors on the lumbar vertebrae bones that surround and protect the spinal cord in the lower back region between the rib cage and the pelvic bones.

Certain parts of these lumbar vertebrae, called the posterior elements which include the pars interarticularis, pedicles, and articular process/facet joints that are at unique risk for overload injuries due to repetitive compression forces and somewhat limited blood supplies to these regions.

Courtesy of www.studyblue.com

In medical terms, we would call pain coming from these movements extension or rotational-based lower back pain, and it thus would seem very logical then to focus evaluation and treatment on the lumbar spine mechanics themselves.

However, my experience in working with higher level volleyball players has taught me that often the dominant shoulder can be a primary contributing culprit to this extension or rotational-based back problem, so now when I evaluate any such type of back pain in a volleyball player, I start by looking at the shoulder.

There are commonly two types of shoulder tightness patterns that can lead to both shoulder problems and pain at the lumber spine.

- TIGHTNESS OF THE FRONT OF THE SHOULDER AT THE CORACOID PROCESS

The pectoralis minor, coracobrachialis and biceps short head muscles all attach to the coracoid process, which is a bone prominent coming off of the scapula.

Courtesy of fashions-cloud.com

Tightness at this attachment site can create a hunched over posture that moms always like to warn about, but also can limit the ability to raise and reach back the shoulder which provides the power needed to hit a ball at the high end of a set or the toss before serve.

If a player has limited flexibility in the front of the shoulder at the coracoid, one frequent way to compensate (or some would say, cheat) is to over-rotate at the lumbar spine in an effort to get the hitting hand far back enough to generate powerful hits or serves.

This over-rotation, while at first might allow the player to maintain high performance, may ultimately cause higher cumulative overload forces on those posterior elements of the lumbar vertebrae and those undesired stress injuries.

This condition causes pain EARLY (before ball contact) in the hitting or serving motions, and proper identification and correction of tightness at the coracoid process can lead to healthier shoulder and back function.

- TIGHTNESS OF POSTERIOR SHOULDER CAPSULE

The glenohumeral joint is the "ball and socket" joint that is surrounded by a soft tissue joint capsule.

Courtesy of heyyoungbeliever.com

Repetitive overhead motion such as hitting or serving can lead to tightness in the back of this capsule, leading to limitations in shoulder internal rotation or the follow-through phase after ball contact.

Called Glenohumeral Internal Rotation Deficit (GIRD), this tightness can lead to reduced accuracy and speed of hits/serves.

Many volleyball players will compensate (aka cheat) by increasing rotation of the lumber spine away from the side of ball after making contact, and eventually this too will place unwanted forces on those posterior elements of the lumbar vertebrae.

GIRD causes pain LATER (after ball contact) in the hitting or serving motions, and just like with anterior shoulder tightness, proper identification and correction can reduce both shoulder and back issues while allowing more high level function.

PRE-EMPTIVE PREVENTION

Volleyball players do not have to wait for the onset of back or shoulder pain to address potential problems. Fairly quick measurements of both anterior and posterior shoulder motion patterns can lead to suggestions for stretching programs, and I routinely incorporate these into pre-season or pre-participation evaluations as part of sensible injury prevention programs.

Learn More On the Current State of Pediatric Sports Medicine: Workforce Analysis Co-Authored by Dr. Koutures

Thanks to co-authors Glenn Engelman and Aaron Provance for their diligent efforts in producing this paper on The Current State of Pediatric Sports Medicine: A Workforce Analysis published in the Physician and SportsMedicine.

Click here to access a PDF copy of the article.

Abstract

Objective: Pediatric sports medicine is an evolving pediatric subspecialty. No workforce data currently exists describing the current state of pediatric sports medicine. The goal of this survey is to contribute information to the practicing pediatric sports medicine specialist, employers and other stakeholders regarding the current state of pediatric sports medicine.

Methods: The Workforce Survey was conducted by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Division of Workforce and Medical Education Policy (WMEP) and included a 44-item standard questionnaire online addressing training, clinical practice and demographic characteristics as well as the 24-item AAP Council on Sports Medicine and Fitness (COSMF) questionnaire. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize all survey responses. Bivariate relationships were tested for statistical significance using Chi square.

Results: 145 surveys were returned, which represented a 52.7% response rate for eligible COSMF members and board certified non-council responders. The most common site of employment among respondents was university-based clinics. The respondents board certified in sports medicine were significantly more likely to perform fracture management, casting and splinting, neuropsychological testing and injections compared to those not board certified in sports medicine. A large proportion of respondents held an academic/medical school appointment. Increases were noted in both patient volume and the complexity of the injuries the specialists were treating.

Conclusion: This pediatric sports medicine workforce study provides previously unappreciated insight into practice arrangements, weekly duties, procedures, number of patients seen, referral patterns, and potential future trends of the pediatric sports medicine specialist.

Three Sports Medicine Articles Co-Edited by Dr Koutures in January, 2016 Pediatric Annals

Pleased to see publication of three outstanding articles on Reducing Cumulative Arm Overuse Injuries in Young Throwers, En Pointe Readiness, and EKG Screening in Athletes for the January, 2016 edition of Pediatric Annals. This Sports Medicine themed edition is the first of a 2 part series, with the second set of articles running in February, 2016.

Some of the following content may require a subscription to Pediatric Annals for full access.

Click here to access my Guest Editorial co-written by trusted friend and colleague Valarie Wong, MD

The discipline of pediatric sports medicine deals not just with musculoskeletal care, but rather encompasses a host of medical and orthopedic concerns to optimize safe and lifelong participation in sports and activities. Pediatric health care providers' well-known general medical and anticipatory guidance skills absolutely make them a natural and trusted part of the sports medicine team.

lick here to access the article: Reducing Cumulative Arm Overuse Injuries in Young Throwers by John Schlechter, DO

Overuse injuries are preventable when underlying contributors (GIRD, scapula dyskinesis) are addressed and enforced pitch counts are consistent with recommended limits. The single most important and modifiable risk factor in preventing injury in young throwers is activity modification and adequate rest periods prior to the onset of arm pain.

Click here to access the article: Assessing Readiness for En Pointe in Young Ballet Dancers by Jeffrey Lai, MD and David Kruse, MD

As with any medical evaluation, a proper history and physical examination are the first steps in assessing readiness for dancing en pointe. Age, years of dance training, and hours per week of training are important details to collect during the history, as are the ballerina's dance aspirations. Prior injuries, especially to the lumbar spine, hips, knees, feet, and ankles, should be recorded. The physical examination focuses on anatomy and flexibility, whereas functional assessments of technique, strength, and postural control also help determine pointe readiness

Click here to access the article: Use of Electrocardiogram as Part of the Preparticipation Exam by Kelly Chain, MD and Andrew Gregory, MD

Sudden cardiac death (SCD) is the leading cause of death in young athletes during sports participation. During preparticipation evaluation (PPE) visits, clinicians are receiving more questions about incorporating electrocardiogram (EKG) screening to detect potentially lethal heart conditions. Many families are aware that several countries in Europe routinely use EKG screening and wonder why the United States has not instituted this recommendation. What are the pros and cons of preparticipation EKG screening in the US, and how might athlete-specific criteria assist in reviewing EKGs conducted in young athletes?

Practical Recommendations for dealing with a Sports Concussion

CONCUSSION INFORMATION

Listed below are informative blog posts with practical discussions of common sport-related concussion symptoms and concerns with helpful treatment recommendations. Please click on each bullet point below to access the particular article

Concussions do not necessarily require being hit in the head or getting knocked out. The full definition of a concussion is any fall, blow, or trauma that causes physical, emotion, or mental changes with or without loss of consciousness.

With formal names like Convergence Insufficiency and Saccadic Dysfunction you might indeed think that this stuff is far too technical to grasp, but in reality, these issues strike at the very heart of some basic life functions.

Experts Debate: How Many Concussion are Too Many for an Athlete?

In the midst of the usual complexities of recovering from a sports-related concussion, I have found that one simple mantra of "re-start activity in 15-20 minutes blocks" can be an anxiety reducing guideline.

Given that headaches are the most common symptom after concussion and often the last to fully resolve, I spend a good amount of time with my patients discussing headache triggers, anticipated healing course, and how to reduce intensity and duration

Top Nutrition Concerns Seen in Adolescent Sports Medicine

Trying to figure if your young athlete needs iron to boost performance?

Uncertain if water or sports drinks would be be the best choice for the next practice or game?

Looking for healthy post-game snacks that will assist in muscle recovery?

Hearing a lot about protein and creatine supplements but not sure if adolescent athletes should use them?

You've come to the right place for practical answers to these and many other nutrition questions that I regularly hear in my sports medicine practice.

In appreciation of CHOC Children's Hospital inviting me to speak on Top Sports Nutrition Concerns Seen in Adolescent Sports Medicine first at their RDs in Practice – Pediatric Sports Nutrition conference and following up with a Pediatric Grand Rounds on the same subject, figured I would compile a list of past blog posts that will form the backbone of those presentations.

Should I Take Extra Iron to Boost My Performance?

What is the Best Fluid Choice for Young Athletes?

Chocolate Milk: A Solid Post-Game Snack Choice

5 Sensible Tips Guiding Nutrition and Recovery After Exercise

What is the Role Of Iron Supplementation in Non-Anemic Endurance Athletes?

General Nutrition Guidelines from Children and Sports Guide

Click on the above links to view the relevant post.

Eager to hear of any additional nutrition or other sports medicine based questions- will offer initial responses via email but always available for office consultations and more in-depth recommendations

Less Football Practice Contact Time May Mean Less Concussions

In the evolving discussion regarding the impact of limited high school contact football practice time on concussion risk, findings from the University of Wisconsin suggest that less contact practices may indeed result in less football-related concussions.

Photo courtesy: http://www.ocregister.com/articles/orange-681360-park-last.html

The state of Wisconsin was one year ahead of California in mandating contact practice time restrictions. Starting with the 2014 high school fall season, the Wisconsin Interscholastic Athletic Association (WIAA) prohibited contact in practice for the first week and limited full contact to 75 minutes per week for week 2, with 60 maximum minutes per week for week three and beyond. These limits are more restrictive than in California where two 90 minute contact practice sessions are allowed per week during the high school football season, thought the definitions of full contact are similar (game speed drills/situations where full tackles are made at competitive pace and players are taken to the ground).

- Click here for related posts on California High School Football Contact Practice limitations.

Licensed Athletic Trainers at several Wisconsin high schools recorded incidence and severity for each sport-related concussion, and compared the two years previous to the rule change (2081 players) with data from the first year of the new limitations (945 players).

Significant findings included

· The rate of sport-related concussion sustained in practice was more than twice as high in the two seasons prior to the rule change

· There was no change in the rate of concussion suffered in games pre and post-rule change

· There was no difference in the severity of concussion (defined as average days lost from football activity) pre (13 days lost) and post-rule change (14 days lost)

· Tackling was the primary mechanism of injury in 46% of sport-related concussions

· Years of football playing experience did not affect the incidence of sport-related concussion in the first year of the new limitations

The authors concluded that limitations on contact during high school football practice may be one effective measure to reduce the incidence of sport-related concussion

How might this relate to California?

This is a well-constructed and much needed initial evaluation on the outcomes of contact practice reductions in high school football, with subsequent years of analysis now being anticipated to see if the above findings hold true over multiple seasons.

The maximum allowed football contact times in Wisconsin are about 42% of the maximal time currently allowed in California, so one may wonder if that increased contact time may make direct extrapolations between the states more difficult. This is where a similar study after the 2015 California high school season is vital to measure the outcomes here in this state.

I was greatly impressed with the finding that there was no change in game-based concussion rate and that the years of previous playing experience not affecting the incidence of new concussion as two potentially landmark outcomes for the future of football safety. Coherent arguments have been voiced that lack of appropriate contact practice time might increase risk for inexperienced or under-prepared players, especially in game time situations. This was particularly voiced for freshman players with no previous tackle football experience. I eagerly await future studies to see if these outcomes are consistent and robust.

The lack of change in severity (again, measured in days lost) brings up a couple of thoughts. The initial reaction might be a bit of disappointment, in that reduction of cumulative head impacts in practice should perhaps lead to a lower burden of injury with a concussive blow and hopefully a quicker recovery. One may not want to try and read much into using number of days lost as a strong measure of severity, for standard return-to-play protocols often mandate a minimum of 8-10 days off from full activity which could influence the return time possibly more than symptoms and other measures of severity.

One important subject not analyzed in this study was the incidence of non-concussion injury rates before and after the practice contact limits were enacted. Concerns have been issued over under-prepared players not confident in tackling techniques or changes in technique (hitting opponent lower in body, for example) both possibly contributing to less concussions, but more shoulder, elbow, knee, leg and other musculoskeletal injuries.

Curious if any groups in California are interested or have proposed a similar analysis of our first year with the high school football practice limitations?

Injuries Seen in Soccer Goalkeepers and How to Reduce the Risk

There is little doubt that goalkeepers are just a bit different than field players.

From being able to legally use their hands to the array of jumping and diving skills needed to keep the ball out of the net, goalkeepers develop a skill set that differs from their counterparts on the field.

Thus, it shouldn’t be surprising to learn that goalkeepers injuries can also be different in terms of causative factors and mechanisms that create risk.

The good news is that goalkeepers statistically don’t get hurt as often as field players, but when some of the goalkeeper-specific injuries do occur, they can significantly interfere with ability to play.

Here is a concise review of common soccer goalkeeper injuries and tips for reducing risks:

- Shoulder/forearm/wrist: Fairly intuitive that after diving and trying to stop balls with the hands, goalkeepers have a far higher chance of suffering shoulder or arm injuries compared to field players

o Fractures to the radius bone are most commonly seen in child and adolescent goalkeepers who have their hands driven backwards towards the wrist when trying to make a save on a direct shot.

§ There is intriguing evidence that balls shot by adults or use of adult size balls (size 5 versus child-based size 3 or 4 balls) may contribute to an increased risk of radius fractures.

§ Risk Reduction Tips: Playing with age-appropriate balls and having adult/older players exercise caution when shooting on younger goalkeepers might reduce radius factures. There is no solid evidence that use of goalkeeper braces or gloves provide adequate reduction for wrist or forearm injuries.

- Hip/groin: Soccer players of all positions are well-versed in the perils of hip and groin pain, and goalkeepers are not immune from this malady, though the mechanisms and types of injury do differ somewhat from field players.

o Side-diving can lead to abrasions (cuts) and bruises on the outside of the thigh region. Most of these are a nuisance, though open skin wounds can become infected and thus need to be watched and cleaned carefully.

§ Older, more professional level players may develop bursitis, which is inflammation of fluid-filled cavities that normally exist around the hip region

§ Risk Reduction Tips: Many goalkeepers used padded shorts for protection, though there is little evidence that both indicates that such padding reduces injury or helps guide selection of particular materials, sizes, or brands to reduce injury risk. Using a rolling motion with diving may reduce loading forces on the hip and thigh region.

o Some studies suggest that injuries to the adductor muscles on the inside of the thigh bone are more apt to occur in goalkeepers than field players, especially on the kicking leg. This might be due to the frequent rotational and leaping movements required in goalkeeping, and also might be worsened by repetitive oversue due to longer goal kicks or punting of the ball.

§ Risk Reduction Tips: Highly recommend the FIFA 11 Soccer Injury Prevention Program which has been developedfor all soccer players above age 14 (not just goalkeepers) to reduce not only hip/groin issues, but also injuries to the thigh,knee and ankle regions.

Limiting the number of longer goal kick repetitions, especially in early season practices with younger players, may reduce the cumulative burden on the hip adductor muscles. Allowing the player to gradually build strength and proper kicking technique may afford more repetitions later in the season.

- Concussion/Head Injury: While goalkeepers do not routinely head the ball, the mere act of jumping or diving in the air places any soccer player at increased vulnerability for head injury due to risk of head impact with other players, the ground, or even the goalposts.

o Goalkeepers also have the additional risks of having close-distance shots directed at them with little time to react or protect the head, or having other players kick them in the head when diving head-first to gain possession of a loose ball.

§ Risk Reduction Tips:

· Using a fist to punch the ball rather than attempt to make a catch in traffic may reduce the risk of either direct contact with other players or limit change of feet being taken out from below

· When going up in the air for a catch, raise elbows to protect the head (but not extending the elbows to impact or injury an opponent)

· Avoid going head-first into ball challenges, better to use feet first approach.

· Officials should enforce a reasonable protective halo distance around diving goalkeepers trying to collect balls to reduce risk of kicks or other direct blows to the head

· With potential close-range shots, teach goalkeepers to have hands up near the face for more immediate potential protection

· Soft protective helmets might reduce the risk of bruises, cuts, and even skull fractures, but they may not be able to limit rotational forces that are thought to contribute the most to concussions. There are also concerns that a player might play more aggressively when wearing a helmet and in theory actually increase rather than decrease the risk of head injury.

Watch Video Below on Reducing Knee Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries for ALL Soccer Players!

15-20 Minute Blocks of Activity: A Guideline for Post-Concussion Recovery

In the midst of the usual complexities of recovering from a sports-related concussion, I have found that one simple mantra of "re-start activity in 15-20 minutes blocks" can be an anxiety reducing guideline..

Looking to return to homework or other school-based activities?

Start with 15-20 minute blocks.

How much can I spend on my phone?

Start with 15-20 minute blocks.

As we discover that absolute rest and removal from usual duties might be counter-productive to recovery, the counter-concern over returning with too much activity, too quickly, or too soon is valid.

Enter the 15-20 minute block recommendation.

When to start?

Usually within a few days after a concussion, and I will counsel patients that at a "good part" of the day where headaches or other symptoms are at a lower point, they should select one activity to start in a quiet room without other stimulation (loud music, bright outdoor light, texts on phone, etc).

While most young people would immediately select their phone, the usual first choice is light reading from a book or magazine rather than a computer screen.

Set a timer for 15-20 minutes, and once that period passes, stop all activity and take a break.

If successful, try another 15-20 minute block of similar activity again later in the day, and if that goes well, can increase to 20-30 minute blocks the next day.

Don't advise going past the "max" time recommendation. Better to finish "early" without symptoms than to muscle forward, develop a headache, and suffer a setback.

For those trying to decide when to return to school, have found that being able to complete 20-30 minute blocks of work 2-3 times a day is a minimum criteria for considering a partial (likely half-day) return to the classroom.

Once able to do at least 2 blocks of activity per day, can add a block of more "fun" which might include cell phone use, texting, appropriate surfing of internet, music, or even some relatively light video game play.

If unable to get through that initial 15-20 minute block of time due to headache or other symptoms showing up, don't despair.

Take the rest of that day off, and try the next day, again maximizing chances with success by ensuring a quiet distraction-free environment, good food and fluid intake, and hopefully after some restorative sleep.

If a few days of attempting the 15-20 minute activity blocks lead to more failure, then do not hesitate to contact your medical provider for more specific tips and further recommendations.

New California Football Contact Limits Provide Unique Opportunity to Study Effect on Concussions

According to the findings of a study published in the May 4th online edition of JAMA Pediatrics, practice periods are a major source of concussion for the high school football player.

While the actual rate of concussion is higher in game play, just over half of the reported concussions took place during practice times.

The authors suggest that strategies should be implemented to evaluate technique, limit player-to-player contact and overall head impact exposures, and reduce other higher risk practice situations.

While the jury is still out on what constitutes proper technique, the mandates of California Assembly Bill 2127 will afford a vital opportunity to further study the influence of practice time limitations on concussion rates in high school football players.

The bill prohibits high schools from conducting more than 2 full-contact practices per week during the preseason and regular season, and prohibits this full-contact portion of the practice from exceeding 90 minutes in a single day.

To clarify, "full-contact practice" means a practice where drills or live action is conducted that involves collisions at game speed, where players execute tackles and other activity that is typical of an actual tackle football game.

Based on the findings of the above JAMA Pediatrics study, the hypothesis is that these new restrictions should reduce concussion rates in practice simply by limiting exposure time and cumulative risk.

Now, one might ask, why would there possibly not be a reduction in concussion rates?

- Is there a chance that limited practice times could lead to less comfort with tackling that could result in an actual higher game rate of concussion?

- Could football programs feel pressure to get in as much contact as possible during the 2 allocated 90 minutes practice periods, possibly leading to more cumulative exposure during that time?

A multi-location review of concussion rates (game and practice) is essential to confirm the effects of California AB 2127.

In such a study, I would also suggest that concussion rates be broken down by academic grade of player, and even take into account years of experience of tackle football.

I wonder if neophytes (namely incoming freshman) who have never previously played tackle football could be at higher risk from contact practice time limits. Would the contact time restrictions have less influence on upperclassman who have played tackle football for a longer period of time?

All stakeholders will be eager to see if indeed there is a documented reduction in overall concussion rates, and if such a reduction is seen across all levels of high school football.

Can Vision Training Reduce Concussions?

While laudable efforts have been put into recognition, evaluation and treatment of a concussed athlete, those are all secondary prevention things done after the injury has already occurred.

Ideally, anything that can be done in the primary prevention world to stop concussions in the first place would be held in the highest of regard.

Helmets and other types of head gear unfortunately haven't served a sufficient protective role.

Now, there are efforts to look at the potential role of Visual Training to Reduce Concussion Incidence in Football, and pardon the pun, the results are eye-opening.

Over the course of 4 football seasons, researchers at a Division 1 Football institution used light board training, strobe glasses, and tracking drills during pre-season summer camp and followed with weekly light board training during the season.

Findings indicated an association of a decreased incidence of concussion among football players during the competitive seasons where vision training was performed as part of the preseason training. The authors suggest that better field awareness gained from vision training may assist in preparatory awareness to avoid concussion-causing injuries.

The research team did caution that this is an exploratory study and asked that future large scale clinical trials be performed to confirm the effects noted in this preliminary report.

What are my thoughts on this study?

- I recall a discussion with a colleague regarding apparent increased in both number and complexity of concussed young athletes compared with 5-10 years ago. There is little doubt that increased concussion awareness accounts for higher patients numbers, but what about the complexity? One offered answer surrounded the extent of visual stimulation required of students today- from tablets to smartphones, from more screen time and power point presentations- visual overload can lead to lower threshold for head injury. While this hasn't been strictly proven, the findings of the above study could lend support to more effective visual processing and perhaps less overall eye strain may be protective against concussions.

- The study does compare head injury rates in the four years prior to the study and those found in the four years with the visual training intervention. There were coaching changes and thus possibly differences in contact exposures between the before and after groups. Trying to compare the reported rates of concussion between this institution and other Division 1 school can be difficult- many programs are very guarded with injury rates, especially when it comes to concussion. All reported concussion numbers (pre/post) seem somewhat low, but again, hard to make an exact statement due to lack of comparison data.

- If these results are validated, I have to wonder if teams will invest the time and energy to adopt such a program. Knee injury reduction programs have been developed with solid supporting evidence, but use by teams lags sorely lags. Concussions are obviously a big deal, so I'd like to think that credible prevention programs would be readily put into place, but part of me has doubts from this past experience.

- Agree with the study authors that this is a preliminary study that merits further investigation with more schools and players of different ages. Not ready to run out and ask schools to invest in the visual training equipment and protocols just yet, but quite eager to see if others can reproduce these results.

I think all of us in the sports medicine world are looking for evidence-based techniques to reduce/prevent concussions. Do the results of the above study seem reasonable to you? Would your team or group be willing to put in the time investment if such a program proved able to limit concussions?

Recommendations for Children and Distance Running

The risks of injury and illness in distance running may be related to the total mileage and number of hours training per week. There is no agreement amongst sports medicine professionals about distance limitations for children. Until further data are available concerning the relative risk of endurance running at different ages, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that if children who enjoy distance running and make the individual choice to train free of injury or ailments, there is no reason to preclude them from training for and participating in such events.

Let me re-emphasize that bold point.

Children should be the ones selecting to run, free of any pressure from peers, parents, coaches or other influences.

Most running injuries include overload injuries to muscles and bones of the legs and feet, and there is the real emotional "burnout" injury from excessive exposure to running.

Concerns have been raised over possible damage to bone growth plates from high amounts of running, but examples of this type of injury have not been consistently found in medical studies.

Looking at running injury patterns and statistics, it is fair to say that when the young athlete is generating the interest and eagerly participating in a sensible training progression, there is a fairly low risk of physical or emotional injury.

To help develop an appropriate program, many recommend using the 10 percent rule is an appropriate guide and considering certain variables:

- Weekly running distance

- Intensity (range includes long slow runs to hill training to speed work)

- Number of training days per week

An athlete should only increase one of those three variables, and no more than a 10 percent increase from the previous week.

Not having number of training hours per week exceed the number of years in the child's age has also been shown to reduce the risk of overload injury.

A comprehensive program should also ensure adequate sleep and nutritional support that can assist with recovery from training.

Consuming protein right after exercise (one gram of protein for roughly every 2 pound of body weight) can assist with muscle repair and recovery. Chocolate milk is a particularly good choice along with Greek yogurt or peanut butter.

Finally, putting more focus on developing the running experience and less on competitive outcomes (medals won, finish times) very likely will reduce the risk of injury and foster a more productive healthy outlook on running for the young athlete.

Lower Rib Pain in Athletes

Have recently seen an interesting group of patients with significant lower rib area pain.

The pain is most often found either on the right or left side, and is particularly noted at the lowest of the twelve ribs. There might be a mass or finger-tip area of discomfort, while in others there is the pain is more spread out and may even move toward the flank or shoulder blade region. Sometimes, the lowest few ribs actually "pop' or have excessive mobility on physical examination.

Don't tend to hear of any changes in appetite or bowel function, and if there is any evaluation of the organs or function of the abdominal cavity (liver, intestines, etc), this tends to be fairly unremarkable.

I definitely do hear about how certain body movements that can trigger issues. For some it is bending forward at the waist, while others are limited with turning/rotating or leaning back.

Here is another important commonality- they all are overhead athletes.

One is a swimmer, the next is a softball pitcher, and a third is a volleyball middle blocker, and yet another is a dancer.

As I have worked with each of them and recreate particular positions that bring about discomfort, it becomes glaringly apparent that shoulder region dysfunction is a strong contributor to the rib pain.

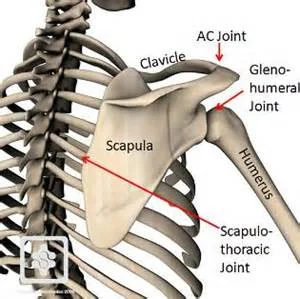

Now if you realize that there are three joints that make up the shoulder region, and one of them involves the scapula (wingbone) interaction with the rib cage, then the association between rib pain and shoulder function should become more clear.

Courtesy of: conornordengren.com/2011/10/14/the-shoulder-girdle-part-1-bones-and-joints-2/

- Lower rib pain on the same side as the dominant arm, such as in a softball thrower or the volleyball hitter, often is due to tightness in the front of the shoulder that limits external rotation and eventually strength and power to hit or throw an object. To compensate for this lack of shoulder external rotation, the entire trunk may over-rotate in the direction of the dominant arm, placing abnormal traction forces on the abdominal muscles that attach to the lower rib area

- Lower rib pain on the opposite side of the dominant arm often is due to tightness in the back of the shoulder glenohumeral joint that limits the follow through phase after hitting or throwing. To compensate, the entire trunk may over rotate to the side opposite the dominant arm and place abnormal traction forces on the abdominal muscles that attach to that opposite side lower rib area.

- Swimmers and dancers tend to equally use both arms and thus might have pain on either side. Looking at the scapula position on the rib cage along with tightness in the front and back of the shoulder is essential to identifying causes of abnormal forces on the lower rib region.

Once these functional issues have been identified, have found that the combination of several management concepts can contribute to resolution of the lower rib pain:

- Appropriate activity modification (limited hitting, throwing, or other provocative positions that trigger the lower rib pain)

- Focus on increasing flexibility of the front/back of the shoulder along with addressing muscle firing patterns around the scapula

- Evaluation of movement patterns in thoracic and lumbar spine that may be contributing to abnormalities at shoulder and lower rib area

- Topical pain relief to lower rib area

- This may include topical or injected anti-inflammatory medications, hot/cold, local friction massage, and acupuncture

These type of cases illustrate the importance of considering dysfunction in regions above or below the area of pain, and how the interaction of different joints continues to be a fascinating challenge for sports medicine specialists.

The above information is meant to illustrate past experience and is not meant to diagnose or act as a substitute for proper, individualized evaluation by a medical professional. It also does not guarantee the accuracy or outcomes of any diagnosis. Please do not hesitate to contact your sports medicine specialist for more information.

Protecting Adolescent Pitchers

If you happen to know an adolescent pitcher who has the fortune of being taller or throwing harder than his peers, chances are that he is perceived as a valuable asset on the diamond. Often this attention and demand may lead to requests to play on multiple teams at the same time.

Unfortunately, these unique characteristics may also lead to an increased risk of shoulder and elbow injuries that could derail the promise of future enjoyment of baseball.

A video analysis of 420 adolescent baseball players along with review of pitching and injury histories found that for each 10-inch increase in a pitcher's height, 10 mile-per-hour increase in pitch velocity, or play for more than one team all significantly increased the risk of arm or shoulder injuries.

Does this mean that having a gun for an arm is a bad thing? Is being tall a negative in the injury world?

I think the reality is that anything that makes a young thrower stand out from peers leads to the temptation of overload and the resultant overuse arm and shoulder injuries.

If proper perspective and patience is exercised, then less chance for badness down the road. However, if combination of all those talents mean requests for more appearances on the mound, playing for more than one team, and thus less overall rest periods, then that is when the problems begin.

It is a natural to want to showcase talents, but for those who are blessed with certain gifts, ensuring appropriate rest during key developmental years can ward off those unwanted outcomes and lead to more enjoyment down the road.

.

Chocolate Milk: A Solid Post-Game Snack Choice

Looking for an inexpensive post-exercise or post-game snack that aids in muscle recovery, delivers several key nutritional components, tastes pretty good, and will make both young athletes and their parents happy with your choice?

Look no further than chocolate milk.

Now, some might say that I have an inherent bias towards chocolate milk due to my medical school and residency years in the dairy state of Wisconsin followed by work in California (another prime milk producing region).

However, when one looks at the science, chocolate milk carries a fair amount of support.

- Chocolate milk has about 26 grams of carbohydrate and 8 grams of protein for a carbo:protein ratio that is fairly close to the 4:1 figure touted by experts to provide necessary substrates for glycogen replenishment and muscle/tissue repair after exercise.

- Reviews comparing chocolate milk to other recovery drinks including water or sports beverages found that chocolate milk may be as effective if not superior in promoting post-exercise recovery specifically by increasing post-exercise muscle protein building with an increased time to exhaustion with exercise.

- Chocolate milk can be viewed as a more accessible and more affordable recovery beverage for many athletes, taking the place of more expensive commercially available recovery beverages.

What's even more exciting is that not only does one get the benefits of post-exercise carbohydrate (this is one form of carbohydrate intake that can be endorsed even by a low carb diet advocate such as me) and protein, but let's not fail to mention other essential nutrients found in chocolate milk:

- With about 150 milligrams of sodium and 425 milligrams of potassium in a typical 8 ounce serving. chocolate milk can replace sweat losses of these key elements.

- Chocolate milk also contains about 300 milligrams of calcium that is more easily absorbed that other forms of calcium in food or supplements. Given the importance of adequate calcium intake especially for teenage females (about 1500 milligrams/day), chocolate milk can provide a significant daily contribution.

- Vitamin D fortified chocolate milk can provide 100 international units of Vitamin D/8 ounce serving to acts as a key component for bone health.

So when it comes time for your post-game snack duty, or if looking for a favorable post-exercise recovery beverage, again, look no further than chocolate milk and don't forget to take in a few final key thoughts:

- Best to drink chocolate milk within 30 minutes of finishing exercise.

- Low fat chocolate milk has been studied the most, though overall fat content should not affect carbo:protein ratio or amount of other nutrients.

- If cannot tolerate or allergic to cow-based milk, can try alternatives such as almond, soy, or rice milk products.

- Best if served cold to enhance enjoyment.

Studying Role of High School Principals in Return to Learn after Concussion

If there isn't enough frustration and feeling of being overwhelmed after suffering a concussion, the process of returning a student back to academic work can only seem to magnify those concerns.

While return-to-play progression protocols have been established to assist in getting athletes back to sport, similar return-to-learn programs have lagged behind. The sheer complexity of meeting particular needs and schedule demands of each student requires an individualized plan created with appropriate understanding of expectations and optimal communication between medical professionals, families and educators.

Often, recommendations include designating a point person who can advocate for the student and family by communication with fellow educators and monitor of student progress. This same person might also provide on-going dialogue with outside medical providers. However, finding a person with appropriate knowledge and desire to accept and carry out these roles can be difficult.

A school-based concussion management and response plan can provide further framework to delineate expectations, potential adjustments, and roles, though the actual implementation and utility of such plans has not received much study.

Given the common findings of frustration and lack of apparent coordination in the return to learn process, I was excited to review the article HIgh School Principals' Resources, Knowledge, and Practices regarding the Returning Student with Concussion in an effort to gain unique and previously unreported insight into school-based resources and management strategies.

Using a cross-sectional computer-based survey of 465 urban, suburban, and rural public high school principals in the state of Ohio, key findings of this study included:

- Just over 1/3 of the principals had completed some form of concussion training in the past year, with those who completed such training have higher self-reported concussion knowledge scores and were more likely to have provided or supported concussion training for school faculty who were not directly involved with youth sports

- When identifying a point person, athletic trainers were most often reported, but about 1/5 of respondents did not know or designate a point person at their school. Schools that identified more than one point person tended to have more students, a principal with higher self-reported concussion knowledge, and to have a full or part-time athletic trainer.

- Athletic trainers were reported as the main agents of communication with medical professionals for concussed student-athletes, while school nurses and counselors assumed this role for concussed students who were not athletes. Principals, assistant principals, and guidance counselors assumed the primary role of communication with parents for all students (regardless of athlete status).

- When asked to respond to a list of short-term classroom adjustments commonly recommended for concussed students, over 90% of principals agreed with all or most of them, with just over 30% requiring a health care provider note to initiate the adjustments.

- Several principals reported a school response-to-intervention (RTI) team to assess student needs and to develop an intervention plan in terms of academic adjustments and accommodations.

- About 1/3 of the schools had a written concussion plan, with 75% of those plans addressing academic adjustments and accommodations.

How can we use these findings to better assist our concussed students in their effort to return to the classroom?

- A principal with concussion knowledge is essential- thus ensure more (and hopefully higher quality) concussion training for principals, which could then translate to more training for school personnel, the identification of point persons to assist concussed students, and better communication between principals and the parents of a concussed athlete.

- An athletic trainer is essential- thus ensure that every high school campus has a certified athletic trainer acting as an advocate for concussed students and being on campus for part/all of the academic day (not just for after-school activities) to foster relationships with teachers and help monitor student developments.

- An intervention team is essential to initiate academic adjustments early after a concussion, preferably without the absolute need of a medical provider note to reduce any obstacles.

- Providing a concussion management plan that delineates roles and expectations and is shared with all key parties (students, school personnel, families and medical providers) to provide education and on-going assessment of the utility of the plan.

What other recommendations do you have to assist concussed students return to learn? Do these recommendations seem reasonable and practical?

Three Cheers for Cheerleading Safety Tips

Cheerleaders such as bases, flyers, backspots and tumblers need agility, strength, and frequent practice to fine-tune routines and prevent injury. Unfortunately, the frequency of cheerleading injuries is rising with the increasing complexity of stunts.

How can cheerleaders, advisors, parents and coaches reduce these injury risks?

- Practice should take place in proper environments: use mats to practice landings and dismounts, and have high ceilings for jumping and throwing routines.

- Experienced and knowledgeable instructors should be consulted to teach the basics of cheerleading in an individualized and step-wise fashion for all participants.

- Coaches should be trained in first aid, CPR, and not hesitate to collaborate with sports medicine personnel such as certified athletic trainers to prevent, evaluate, and properly manage cheer-related injuries.

- A base must know how to support a flyer without hurting him/herself, while the flyer must know how to land safely.

- Teach flyers rolling and landing techniques over and over again.

- Bases need to work on using their legs, buttock and posterior hip regions for proper lifting and holding techniques that reduce cumulative trauma to shoulders and the back.

- Tumblers should develop appropriate strength in the back of the shoulders and hip regions to take pressure off elbows, wrists, and knees.

- Pre-season conditioning is essential with focus on shoulder, hip and back strengthening exercises. An athletic trainer, physical therapist, or sports medicine physician can demonstrate and recommend appropriate conditioning programs.

- Encourage necessary recovery by regularly scheduling rest periods (at least one off day a week during season and at least 2-3 months a year off of cheerleading activities).

- Avoid multi-level pyramids or throwing of cheerleaders unless all participants are comfortable and well-trained in these skills. One weak link can ruin the routine for all others.

- If there is pain or discomfort with any portion of a routine, do not compromise personal safety or the safety of teammates. Work with a coach or obtain medical evaluation before returning to practice or competition.

- Once returning from a injury, a cheerleader should go through a progressive step-wise return by first working on individual skills such as tumbling, kicks, and tucks before moving to group activities and finally stunting.

Do you have any more suggestions for cheerleading safety tips?

Injury Prevention Tips for Adolescent Dancers

The following Injury Prevention Guidelines summarize findings from the article The Adolescent Dancer: Common Medical Conditions and Relevant Anticipatory Guidance by Kathleen Linzmeier, MD and Dr. Koutures which is published in Adolescent Medicine State of the Art Reviews, April 2015 and is copyright from the American Academy of Pediatrics.

1) The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends a rest period from organized physical activity that includes a minimum of 1 full day off per week and 2 to 3 months off per year.

3) Single sport or activity specialization at young ages can increase the risk of physical and emotional overuse, frequently leading to burnout and complete cessation of activity. Particular warning signs may include decreased interest in dance activities, lower school grades and attendance, less social interaction, changes in appetite or sleep, and mood alterations such as irritability, anger, or lack of fun or new activities.

4) Incorporating recommended weekly and annual rest intervals along with varying the types of organized activities can reduce the potential for burnout.

5) Medical practitioners may be asked for their opinion on the readiness of young dancers to begin dancing en pointe, which is an advanced ballet skill that places extreme stress on the lower leg, ankle, and foot

6) Readiness recommendations focus not on chronologic age but on the presence of adequate whole body strength and balance (especially of the foot and ankle), lack of current restricting injuries, sufficient “pre-pointe” dance class exposure (minimum 3-4 years), and the future goals of the dancer.

7) Medical professionals should maintain an open dialogue about adequate intake of calories and essential vitamins and minerals, and maintenance of healthy weight to best support ongoing dance activities.

8) Physicians should respect the anatomic and emotional changes that occur during puberty without hesitating to modify or change focus to more basic skills to allow compensation for changes in movement patterns and coordination.