Filtering by Tag: dance medicine in orange county

Turns, Jumping and Landing: Shin and Foot Injuries in Dancers

http://chapman.edu/copa/dance/

The following article is an edited version of a chapter on Adolescent Dance Medicine co-written by Dr. Koutures and Kathleen LInzmeier, MD in Adolescent Medicine: State of the Art Reviews, Vol 26 No 1 published by the American Academy of Pediatrics in April, 2015. This information is not designed to suggest or confirm any individual diagnosis. Any injury deserves complete evaluation by a dance medicine specialist.

Advanced ballet dancers spend a great deal of time en pointe, which puts them at risk for foot injuries while in full en pointe and ankle injuries while in slight dorsiflexion (known as demi-pointe). While in full en pointe position, the ankle is relatively stable since the posterior lip of the tibia rests and locks on the calcaneus and the subtalar joint is locked with the heel in forefoot.

A dancer is more likely to acquire a midfoot than ankle sprain while in en pointe. Midfoot sprains result from a loss of balance while en pointe and performing spins. Lisfranc injuries involve fractures or fracture-dislocations in the middle of the foot at the base of the long metatarsal bones. Less common midfoot injuries include injuries to the dorsal ligaments between talus and navicular or the calcaneus and cuboid.

- GOAL: Seek immediate medical care with any twisting injury of the middle of the foot that results in pain, swelling or feeling of limited stability

The ankle is vulnerable to inversion injury when moving into slight dorsiflexion from en pointe position. As the ankle progressively inverts greater pressure is placed on the lateral ankle ligaments, particularly the anterior talofibular ligament. The talus is wider anteriorly and more narrow posteriorly. The inherent instability of the more narrow posterior talus combined with the vertical alignment of the anterior talofibular ligament make the ankle at risk for inversion while in plantarflexion but not fully in the more stable en point position.

Underlying hypermobility and prior history of ankle sprains are strong predictive factor for ankle sprains. Hypermobility of the ankle joint causes forces at the foot to be transferred proximally in suboptimal fashion thus leading to injury. The incidence of recurrent injury after initial acute ankle sprain has been reported to be as high as 70%. Ankle sprains lead to reduced subtalar and ankle motion which can lead to resultant increased compensatory stresses on muscle tendon units contributing to repetitive injury. Impaired balance and proprioception can additionally follow ankle sprains and can last for up to 2 weeks following injury despite active rehabilitation.

- GOAL: Take appropriate time and get experienced guidance to allow maximal recovery from ankle sprains as an Increased risk for injury can occur if strength and coordination are not fully restored.

Dancers are additionally susceptible to several unique fractures of the 5th metatarsal bone. Avulsion fracture of the styloid process of the 5th metatarsal, involving a fracture line perpendicular to the long axis of the bone, is associated with lateral ankle sprains as it is usually caused by sudden inversion of the foot. Acute metaphyseal-diaphyseal junction fractures, known as Jones fractures, occur with adduction of the 5th metatarsal often while the foot is plantarflexed and have a predilection for malunion due to the poor blood supply as the metaphyseal-diaphyseal junction is a vascular watershed zone. Oblique spiral fracture through the mid to distal portion of the 5th metatarsal are known as “Dancer’s fractures” and usually occur with twisting or inversion of the foot while on demi pointe.

Repetitive Landing and Jumping Resulting in Foot and Shin Injuries

The repetitive nature of dance training can lead to many overuse injuries involving the feet and shins, especially if dancers have any underlying limiting anatomy, poor form, or insufficient rest. The spectrum of repetitive overload injury can range from soft tissue injury to bone stress reactions (increased bone resorption and production without frank fracture line) and eventually true stress fractures.

Hallux rigidus (reduced motion of the big toe) is caused by repetitive flexion and hyperextension of the metatarsalphalangeal joint. It is usually the result of pronation of the great toe when attempting to force turnout leading to restriction of full dorsiflexion of the first metatarsalphalangeal joint with resultant prominent spur formation on the dorsal aspect of the first metatarsal head that prevents performing full relevé.

- Many dancers with reduced first big toe motion accommodate for this limitation by putting more pressure on the outside of the foot, which can lead to ankle sprains and fractures of the fifth metatarsal.

- GOAL: Increase first toe range of motion to reduce abnormal forces on the outside of the foot and also at the ankle, knee and hip

Shin splints, or medial tibial stress syndrome, describe a traction periostitis that is associated with diffuse anteromedial or posteromedial tibial pain that typically involves the distal one third of the tibia. While medial tibial stress syndrome occurs at the beginning of the season after a long period of activity, dancers are also prone to tibial stress fractures that usually occur in the middle to late season. Lower risk tibial stress fractures involve the proximal lateral or distal medial tibia. Dancers are also particularly at risk for traction fractures of the anterior tibial cortex that present with acute disability in male dancers after landing from a jump or more gradual onset in female dancers who might have poor bone health.

The sesamoids are particularly at risk for stress injury given their vulnerable location beneath the base of the first metatarsal in the substance of the flexor hallucis brevis tendon. An exaggerated turned out position can also lead to sesamoid overload due to rolling out, which increases medial loading of the first metarsal-phalangeal joint.

- The medial (inside) sesamoid bears more stress both in releve and when dancers walk turned out.

- GOAL: Correct turn out and plie positions so that the middle of the kneecap is over the 2nd toe can reduce stress on sesamoids and the inside of the foot.

Another common site of stress fractures in dancers is the base of the second metatarsal, which is the longest metatarsal and therefore bears the bulk of weight while in demipointe position. The distal aspect of the fibula, usually 10 cm above the lateral malleolus in the distal third of the shaft may also be prone to stress fractures which usually occur in the weight bearing leg and are frequently the result of poor balance and fatigue when initiating a turn.

- GOAL: Any midfoot pain, especially on the top of the arch of the inside of the foot, must be fully assessed for a navicular stress fracture which is a high risk traction injury due to repetitive jumping and landing on a plantarflexed foot.

In the majority of stress fracture injuries plain films are typically negative and diagnosis instead requires Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Rest from loading activities is usually necessary for healing for at least a minimum of 4 weeks, during which a dancer can utilize yoga, pilates, water based exercise and other non-impact forms of rehabilitation to correct biomechanical issues. Higher risk stress fractures, such as the anterior tibial cortex and tarsal navicular, require initial non-weight bearing on the injured limb, prolonged rest (several months) or surgical intervention and have a higher risk of adversely influencing the career of a dancer.

- GOAL: While no performer wants to be removed from dance for any period of time, knowing those situations that require prolonged rest and seeking appropriate specialty care can be the difference between ability to return to dance and the end of a career.

Are there any other dance-related foot or shin injuries that should be mentioned? Do you have any practical tips or experience to help prevent or treat these common dance problems?

Injury Prevention Tips for Adolescent Dancers

The following Injury Prevention Guidelines summarize findings from the article The Adolescent Dancer: Common Medical Conditions and Relevant Anticipatory Guidance by Kathleen Linzmeier, MD and Dr. Koutures which is published in Adolescent Medicine State of the Art Reviews, April 2015 and is copyright from the American Academy of Pediatrics.

1) The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends a rest period from organized physical activity that includes a minimum of 1 full day off per week and 2 to 3 months off per year.

3) Single sport or activity specialization at young ages can increase the risk of physical and emotional overuse, frequently leading to burnout and complete cessation of activity. Particular warning signs may include decreased interest in dance activities, lower school grades and attendance, less social interaction, changes in appetite or sleep, and mood alterations such as irritability, anger, or lack of fun or new activities.

4) Incorporating recommended weekly and annual rest intervals along with varying the types of organized activities can reduce the potential for burnout.

5) Medical practitioners may be asked for their opinion on the readiness of young dancers to begin dancing en pointe, which is an advanced ballet skill that places extreme stress on the lower leg, ankle, and foot

6) Readiness recommendations focus not on chronologic age but on the presence of adequate whole body strength and balance (especially of the foot and ankle), lack of current restricting injuries, sufficient “pre-pointe” dance class exposure (minimum 3-4 years), and the future goals of the dancer.

7) Medical professionals should maintain an open dialogue about adequate intake of calories and essential vitamins and minerals, and maintenance of healthy weight to best support ongoing dance activities.

8) Physicians should respect the anatomic and emotional changes that occur during puberty without hesitating to modify or change focus to more basic skills to allow compensation for changes in movement patterns and coordination.

An Intensive Effort to Reduce and Prevent Dance Injuries

Always a leader in cutting edge dance, Backhaus Dance is also front and center with promoting health dancer practices. Proud to be part of their Summer 2016 Intensive faculty and proud to share tips below with all dancers and dance educators.

Click on each slide to advance.

Peak Athletic Performance Often Leads to Peak Illness Risk

It can be an awesome feeling to be "in the zone" or "performing better than I have in years”.

It however, can be a major downer when that peak performance comes at a cost to immediate health and the immune system.

Anyone who has been around the time of a big show knows how performers like to celebrate afterward. That's right- everyone tends to get sick.

Exchange the big show for the big race or big competition and you often see the same outcome- many athletes go from the podium or finish line to the sick bed. Saw it at the Olympics where my first up close and personal views of gold, silver and bronze medals were around the necks of athletes coming in to the medical unit for upper respiratory infection evaluations.

Those were the fortunate ones who had timed their peak performance to occur at the Games and didn't have unplanned illness interrupt training or competition.

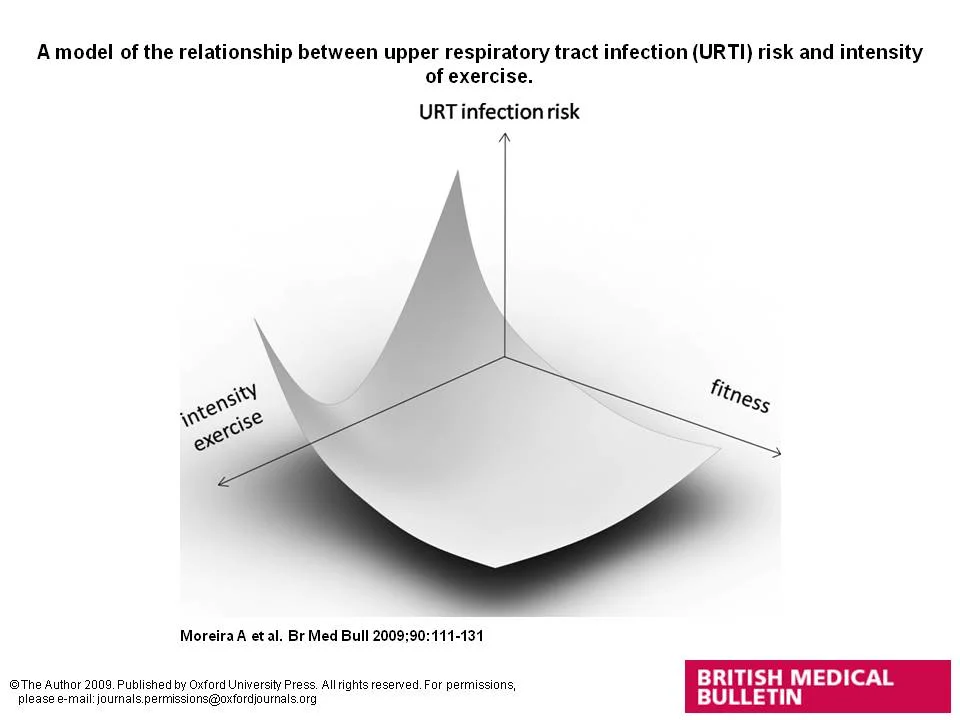

Unfortunately, many times this fairly tale ending doesn't occur. Peak performance earlier in a season leads to mid-season illness and eventual disappointment. Solid evidence tells us that moderate levels of physical exertion are protective against illness, while higher extremes of activity can diminish immune defenses and increase illness risk. Having a solid base of fitness before assuming more rigorous training can also reduce risk of diminished immunity and increased chance of illness.

It is nearly impossible to maintain peak performance for too long, especially over a schedule of multiple events combined with the stressors of school, homework, and a social life.

Trying to get adequate sleep (minimum 8 hours a night), proper nutrition including berries, cherries, and fish for the anti-inflammatory effect, and planned off days from training and competition can help combat the stressors that sap performance.

More important is adhering to the principles of periodization, where well-constructed training blocks are created to allow peaking at optimal times while also maintaining periods of relative rest and recovery.

So, if an athlete tells me "I'm at my best" right before a chosen high level competition, then less cause for concern. Still might get sick afterward, but the merging of preparation and schedule hopefully is fairly favorable.

If an athlete is peaking well before that big competition which is still weeks or months away or with many of my young athletes when they have to get up every week because "every game is a big game", then my worry starts to go up.

Nothing worse than showing up in the doctor's office missing key training days or even worse, important competition time due to illness. Enhancing the immune system with proper rest and recovery can lead to more visits in the winner's circle and less time scheduling visits with the medical staff.

Video: Dr. Koutures Grand Rounds on Performing Arts Medical Care

August 20, 2014 - Grand Rounds - CHOC Children's Hospital

Click Here for Video: The Performing Arts Athlete: Anticipatory Guidance & Evaluation

Chris Koutures, MD, FAAP

Pediatric and Sports Medicine Specialist

Anaheim Hills, CA

Medical Team Physician, Cal State Fullerton and USA National Volleyball Teams

Outcomes - At the conclusion of this presentation, the physician leaner will be able to:

1. Provide anticipatory guidance to young dancers and performers about nutrition, rest, risk of overuse, and other key injury/illness concerns.

2. Appreciate the various forms of dance and recognize certain movements and positions that can lead to both acute and overuse injuries.